The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is facing a water crisis. With demand rising and supply dwindling, the most water-scarce region on the planet is in danger of running dry.

Governments are investing in solutions to increase water supply and safety, including a range of desalination technologies, water and waste-water treatment and recycling, and with this large-scale investment, and its inherent risk, comes a key role for reinsurance.

In this JENOA insights article, we look at the scale of the problem and the projects being developed to solve it.

A worsening crisis?

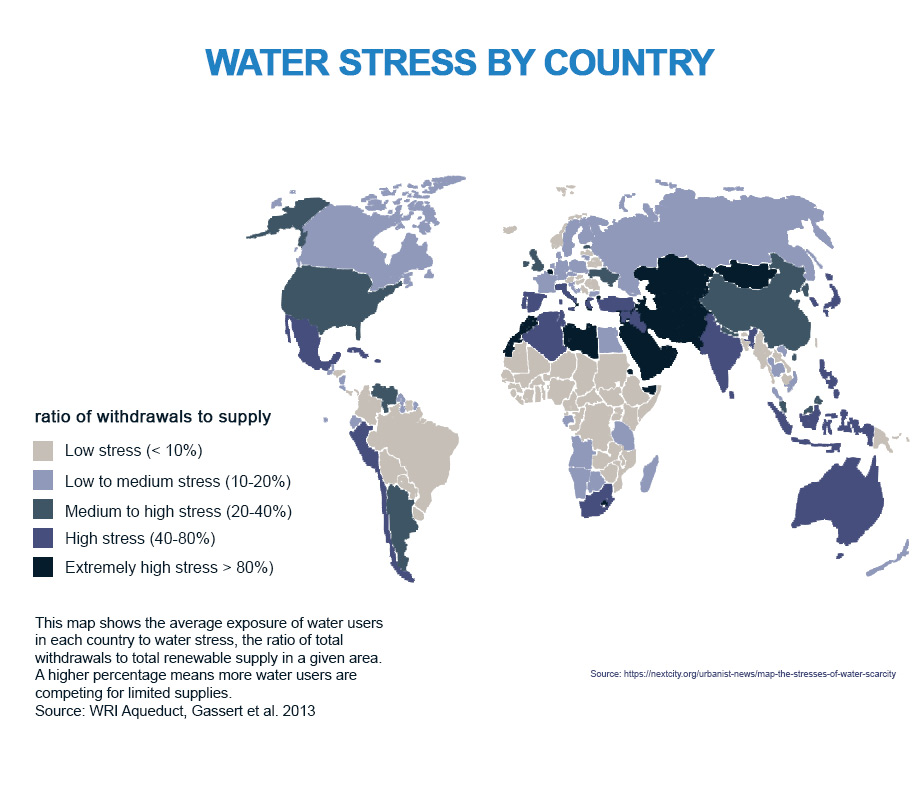

Water – not oil – is undoubtedly our most precious resource. The MENA region includes 12 of the world’s 15 water-scarce countries – those with an average of less than 1,000 cubic metres of water per person, per year (other geographical regions average 7,000).[1][2] It is home to 6.3% of the world’s population, yet only accounts for 1.4% of its renewable freshwater.[3]

The region also has the world’s highest per capita freshwater extraction rate of 804 cubic metres per year[4] and uses more than 75% of its renewable water resources. And, with availability expected to dramatically reduce in future years, two-thirds of MENA countries could have less than 200 cubic metres of renewable water resources per capita per year by 2050.

The shortage is being driven by a surge in demand from MENA’s ever-growing population which has grown from 173.4 million in 1970, and is expected to reach 568 million by 2025,[5] as birth rates rise and the migration from rural to urban areas increases due to the impact of climate change. More frequent and severe weather events, such as droughts and flash floods, have destroyed property, crops, and livelihoods, adding to the pressure on water supply.

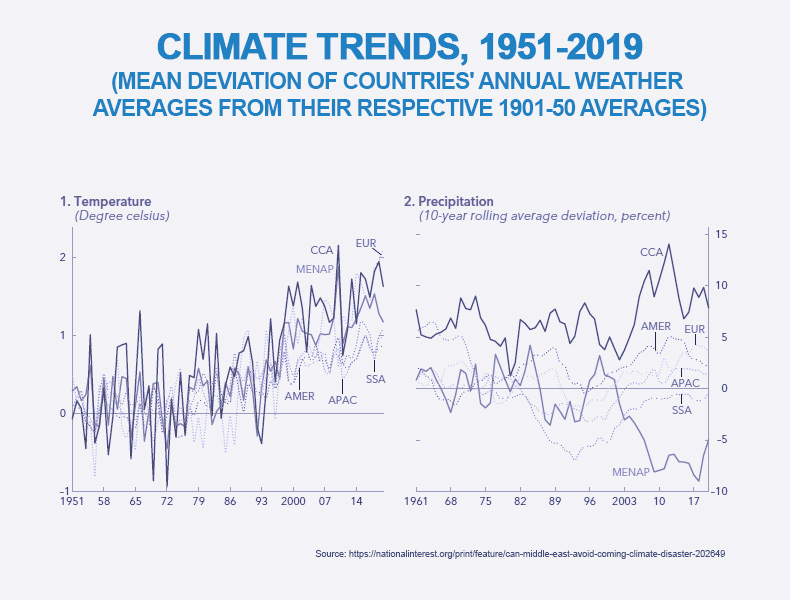

With the region’s average temperature rising 1.5 degrees Celsius since 1990[6] – more than twice the global average – the problem is only going to get worse, with shorter and warmer winters and hotter and drier summers. Furthermore, with rainfall declining and evaporation rising, the region’s internal renewable water is forecast to reduce by around four percent by 2050, with between 80-90 million residents experiencing water insecurity by 2025.

Such is the extent of the problem that 120 disasters were recorded in the region in the last five years alone,[7] resulting in an annual average of US$ 1 billion of damages and losses. Reflecting this, water and extreme weather and natural resource crisis were cited among the top 10 global risks by the World Economic Forum.[8]

What is being done about the problem?

Governments are working with businesses and non-governmental organisations, in public-private partnerships, to develop strategies to increase access to water, while improving the management of existing supplies. The Arab Water Council, for example, has developed six policy briefs for non-conventional water resources (NCWR), including enhanced policy framework; a legal and institutional enabling environment; technical capacity building; social consideration, and economic and financial measures towards NCWR development and management in the region.

Desalination has become one of the fastest adopted methods for increasing supply. Extracting salts and other materials, from seawater, provides a clean, reliable and, at least practically speaking, potentially infinite water source. With the increasing adoption of renewable energy sources in the region, in particular, solar and wind power, together with utility-scale battery energy storage solutions, desalination can become a wholly sustainable and renewable water solution.

MENA has already established itself as a global leader in the process, with seawater desalination contributing to more than 90% of the Gulf Cooperation Council’s daily water requirements. The Gulf States account for 60 per cent of the world’s desalination capacity, with half of that in Saudi Arabia alone, thanks to its facilities on the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. One of the most notable of these, the Shuqaiq 3 desalination plant, has a nominal daily production capacity of 450,000 cubic metres.

Saudi Arabia has recently announced more than 60 water projects worth some US$ 9.3 billion.[9] These will triple daily desalination capacity from 2.54 million cubic metres of water in 2021, to over 7.5 million by 2027. In line with the Country’s National Water Strategy 2030, published in 2018, it is also developing a network of 147 small sewage treatment plants to recycle wastewater.

Alternative water production techniques include qanats and rainwater harvesting, sequential water use, and water trading. Qanats, which are predominantly used in Iran, consist of a series of tunnels bored into a cliff or mountain, which collect water. Elsewhere, rainwater is diverted from roofs, cisterns and other sources into ponds and reservoirs.

Sequential water use involves capturing and treating water that has been used in one sector for consumption in another. For example, urban wastewater can be treated and channeled from urban areas onto nearby farms. Water can also be transported between different regions by boat, pipeline and trucks.

Protecting these new resources and the people who rely on them against the risk of climate induced catastrophe and/or breakdown will require tailor-made insurance and reinsurance solutions. Parametric Insurance, which triggers a pre-specified payout based on the magnitude of any specific event, and microinsurance are emerging as popular products.

They have been particularly effective for farmers and small businesses, enabling them to recover quicker losses caused by the increase in extreme weather events. Risk modelling has also improved the prediction of such events, enabling re/insurers to work more effectively with governments and businesses to develop robust risk management and prevention strategies to address the problem.

More efficient use

With 85% of MENA’s water used for irrigation in agriculture,[10] where its average use efficiency is only 50-60%, big improvements are required. Smart technology, such as drip systems, can be used to control the amount of water used and where it’s allocated. Growing crops using hydroponics, focusing on less water-intensive crops and adding fertiliser to the water can also free up water to be used in other areas.

Building codes that mandate water conservation as part of the design and construction must also be introduced, while faulty or leaking distribution systems need to be repaired or replaced.

On a wider scale, authorities will need to implement new legislative and regulatory policies governing how water is used and managed, following in the footsteps of pioneers such as Egypt, Jordan and Palestine, which have all approved national water resources plans.

Concerted government education programmes on water conservation in schools and public centres can also encourage people to be more environmentally responsible and proactively reduce their daily water consumption. This can be backed up with the installation of smart meters and technology in homes and offices to monitor and optimise usage.

Governments are recognising the need to work together to address the issue. In November 2021, Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian Authority formed the Water-Energy Nexus, a regional water and energy pact aimed at maximising natural resources usage.

With MENA hosting the next two COP climate summits, in Egypt’s Sharm El-Sheikh this year and the UAE in 2023, the region has a golden opportunity to set the agenda for water conservation and management worldwide – and ultimately help to sustainably safeguard its future

[1] https://www.prb.org/resources/finding-the-balance-population-and-water-scarcity-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa/

[2] https://www.ecomena.org/water-conservation-middle-east/

[3] https://www.prb.org/resources/finding-the-balance-population-and-water-scarcity-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa/

[4] https://www.ecomena.org/water-conservation-middle-east/

[5] https://www.prb.org/resources/finding-the-balance-population-and-water-scarcity-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa/

[6] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-30/middle-east-on-course-for-huge-climate-change-losses-imf-says

[7] https://www.mei.edu/publications/could-climate-risk-insurance-reduce-cost-climate-change-adaptation-middle-east

[8] https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-risks-report-2022/digest/

[9] https://smartwatermagazine.com/news/smart-water-magazine/saudi-arabia-announces-60-water-projects-worth-us933-billion

[10] https://www.ecomena.org/water-conservation-middle-east/