Lithium-ion (li-ion) batteries, and more specifically, the electric vehicles (EVs) that use them, have been high on the news agenda since the loss of car-carrying vessel Felicity Ace off the Azores in February 2022. That fire resulted in the total loss of the ship, as well as cargo losses of approximately US$ 400 million,[1] with the vessel finally sinking some 200 miles off the coast of the Azores two weeks after the fire started.[2]

At the end of July this year, yet another car-carrying vessel, the Freemantle Highway, suffered a major fire off the Dutch coast thought to have potentially been started by one of 500 EVs on board.[3] It remains unknown why the operator initially reported that there were only 25 EVs on board before revealing the true extent of its cargo.

With some commercial carriers already beginning to restrict or curtail the types of EV they carry – for example, Wallenius Wilhelmsen[4] refuses to carry used EVs due to their ‘unpredictability’ – how will it impact the marine insurance industry, and what are the implications for the international automotive and passenger-ferry sectors as the world begins the long, slow transition to an electrified bridging technology?

Vessel losses

While the exact cause of the fire on board Felicity Ace may never be officially established, the marine insurance industry remains in little doubt: the rapid spread and perhaps even the original cause of the fire can probably be attributed to the presence of lithium-ion batteries in one or more of the 300 EVs that were being carried alongside around 4,000 other vehicles. While some operators and shippers claim that fire losses cannot with any certainty be attributed exclusively to faulty EVs and argue that they present no greater risk than any other vehicles, the growing incidence of on-board fires accompanied by a sharp rise in the shipping of li-ion batteries has made the insurance industry increasingly sceptical of claims of a mere coincidence. In addition, the fact that the cause of the Felicity Ace loss is still officially unproven – it sank in deep water some 200 miles off the coast of the Azores, making a conclusive report unfeasible – is unlikely to prove an adequate defence for an automotive industry keen to continue with cost-conscious business-as-usual, given the fast-accruing loss history data (see below).

The more recent loss of the Fremantle Highway to fire off the Dutch coast in late July 2023, has added to growing concern in the marine insurance sector surrounding the shipping of EVs and of li-ion cells in general. The vessel was carrying around 4,000 vehicles, of which approximately 500 are thought to have been EVs.[5] The fire caused the death of one crew member as well as significant economic damage and it is almost certain that the vessel will be written off as a constructive total loss.

What does recent loss data tell us?

In 2022, eight vessels were lost to fire, with around 200 reported incidents during the year, which according to Allianz’s Safety and Shipping Review 2023, was the highest figure for a decade. In the last five years alone, some 65 vessels have been lost to fire, and although overall shipping losses have declined by 65% in the last decade – 100 vessels were lost in 2013, compared to only 38 in 2023 – losses due to fire have not followed the same trend. In 2023, fire accounted for nearly 20% of the value of all marine claims.[6]

What are the main issues with li-ion batteries?

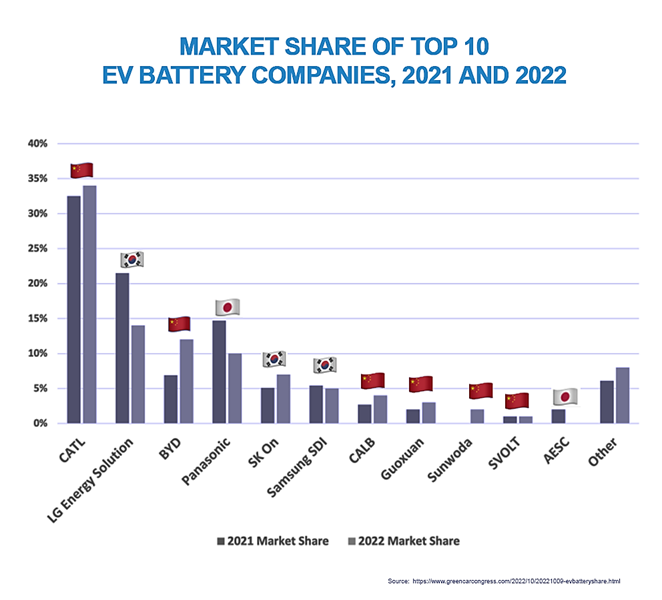

Growth in the EV market has seen a significant rise in the quantity of li-ion batteries being shipped around the world, with almost 9 million units due to be shipped over the course of 2023. With China accounting for approximately 60% of the global trade in EV batteries[7], and South Korea a further 25%, a host of new manufacturers has flooded the market, giving rise to understandable concerns about trade-offs between speed of production and supply, and quality control and attention to safety.

Those concerns have spread to include previously trustworthy European brands, given that the world’s top supplier of EV batteries, China’s CATL, supplies li-ion batteries for OEMs such as Peugeot, BMW, Volkswagen and Volvo. Both the Felicity Ace and Freemantle Highway were carrying well known EV brands such as BMW, Audi, Porsche, Bentley, Rolls Royce and Mercedes Benz, many with batteries manufactured in China. This raises serious questions for the marine insurance sector: as new EVs from European OEMs are being shipped direct from factories to overseas markets – the Felicity Ace was en-route from Germany to the US, and the Freemantle Highway, from Germany to Egypt – why are vehicles fitted with sub-standard, damaged or malfunctioning battery units leaving European factories when the risk to international shipping is so acute? Can anything be done to improve safety monitoring and quality-control without significantly increasing the already high cost of the EV supply chain?

From a combustion perspective, the oxides in the chemical make-up of li-ion cells means that once a fire starts and the unit reaches thermal runaway, the cells produce vast amounts of oxygen to further fuel that fire, and fire can quickly spread between cells. L-ion cells also produce corrosive and poisonous gases that will cause an explosion in a confined space, such as a contained car deck on a vessel. Furthermore, li-ion cells burn more intensely than internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs); the blaze aboard Felicity Ace lasted almost two weeks before it was extinguished due to the vessel sinking in deep water,[8][9] and the fire on the Freemantle Highway burned for a week.

As the global head of marine risk consulting at Allianz Commercial recently pointed out, “it is only when they ignite that they are more difficult to extinguish as they can burn more ferociously and are capable of spontaneously reigniting hours or even days after they have been put out.” He went on to note that the growing problem is exacerbated by the fact that most ships lack the protection, fire-fighting capabilities and detection systems that the increased risk of carrying li-ion cells demands.

The JENOA view: What can the marine insurance sector do to improve the situation?

Pre-emptive measures to mitigate the increasing risk posed by the transport of li-ion cells are urgently needed, and insurance companies will likely begin to broaden and deepen conditions of carriage before cover is provided for car-carrying vessels in the future. According to Allianz, at a conservative estimate, around 25% of all major incidents on board container vessels can be attributed to mis-declared dangerous goods, such as batteries.[10] Hazardous cargo requires enhanced documentation and more rigorous rules for stowage, and the cost savings involved are such that cargo is routinely stowed carrying misleading labelling or documentation. One option that is likely to be adopted by the marine insurance sector is to insist on proper and correct labelling for EVs, under which they must display clear identification on the windshield specifying the battery type – Battery Electric Vehicle (BEV), Hybrid Electric Vehicle (HEV) and Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV), for example.

Another possible condition of carriage that insurers may begin to insist on, relates to the state of charge of the li-ion batteries being carried, and an insistence that the charging of battery electric vehicles is strictly prohibited during passage. L-ion batteries should be charged to little more than 30% capacity, and should never exceed 50% capacity, given the high energy density of a fully charged EV battery.

Proper certification from manufacturers, for both shipping companies and marine insurance cover, is one of the most urgent actions that can be taken to avoid further loss from fire. In an ideal world – and certainly one in which insurance providers can mitigate growing risk – all EVs should carry documentation to demonstrate that they have passed pressure, temperature, crush, and impact tests as set out in the UN Manual of Tests of Criteria for transport of li-ion batteries.

Other measures that will inevitably add significant costs to the industry include enhanced crew training, on-board early detection system upgrades, and innovative but costly fire suppression methods. Fire-proof blankets or containment bags, for example, are being considered by some car-carrier operators, and similar technology has already been tried and tested in aviation, where containment bags contain li-ion thermal runaway in phones, iPads and laptops carried aboard aircraft, as well being able to absorb the force of exploding smartphone li-ion batteries.[11]

The costs, however, may prove prohibitive; given that small fire-containment bags designed for phones onboard aircraft cost in excess of US$ 600 per unit, the additional costs for suitable fire-containment bags for car-carrying vessels with up to 5,000 units on board could run into the tens of millions of dollars just to satisfy insurance terms and conditions.

While the general public has so far been shielded from the dangers of EV-carrying vessels, the marine insurance sector will also need to focus urgent attention on the risks posed to the passenger-ferry industry, where concerns are already beginning to influence operational decisions.

Scandinavian passenger-ferry operator Havila Kystruten decided earlier this year to ban all EVs, hybrids and experimental hydrogen vehicles from its passenger ferries,[12] based on extensive risk assessments on the hazards of carrying non-fossil-fuel vehicles, limited fire-fighting capabilities, the dangers of water-based fire suppression to a vessel’s stability, and the sheer number of passengers at risk from li-ion battery fires.

The worldwide ferry industry association, Interferry estimates that ferries carry over 4 billion passengers and 370 million vehicles annually[13], and the carriage of EVs gives rise to considerably increased exposure to risk for the world’s travelling public and vehicle stock. This raises serious questions for the wider marine insurance sector with regard to the world’s car-carrying passenger-ferry services, from the Scottish Highlands and Islands and the North Atlantic, North Sea and Baltic, to Bangladesh, Indonesia and the Philippines.

How can JENOA help MENA clients?

JENOA has placed the reinsurance program for the largest vehicle marine stock-throughput program in MENA region. By accessing the Lloyd’s of London market in addition to other reinsurance hubs around the world, we can insure the transportation & storage of vehicles including EVs, from the initial port of origin through to the handover to a customer.

We have a strong focus on working with our Clients to meet their strategic business objectives and leverage our global reinsurance capabilities to meet these emerging challenges in the automotive and shipping sectors. We therefore believe JENOA is well positioned to support our MENA clients as they begin to transition towards bridging technologies, that might one day result in lower fossil-fuel use.

What might the future hold?

There is no doubt that the marine insurance sector will respond to increased risk in the shipping of li-ion batteries, notably with increasingly stringent terms and conditions of carriage.

While these measures will inevitably drive-up costs for shippers, automotive manufacturers and, ultimately, the consumer retail market, the fact that shipping companies are already refusing to transport EVs because of increased fire risk should serve to concentrate minds on the best solutions for the future. From the medium- to long-term insurance perspective, those roll-on, roll-off (ro-ro) vessels specifically designed to reduce the risk of a li-ion battery-EV fire, should benefit from reduced marine insurance costs.

[1] https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/scorched-cars-burn-insurers-facing-higher-risks-from-electric-vehicle-transport-69252443

[2] https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/scorched-cars-burn-insurers-facing-higher-risks-from-electric-vehicle-transport-69252443

[3] https://www.tradewindsnews.com/casualties/k-line-reveals-close-to-500-electric-vehicles-on-fire-ravaged-car-carrier-fremantle-highway/2-1-1492734

[4] https://www.thefpa.co.uk/news/ev-ferry-risk-criticism-aimed-at-car-manufacturers

[5] https://gcaptain.com/boskalis-ceo-says-fremantle-highway-fire-started-in-upper-vehicle-decks/

[6] https://www.insurancebusinessmag.com/uk/news/marine/ship-fires-still-top-concern-for-shipping-industry-454294.aspx

[7] https://www.greencarcongress.com/2022/10/20221009-evbatteryshare.html

[8] https://www.autoevolution.com/news/felicity-ace-fire-may-make-cargo-ships-wary-of-transporting-evs-185896.html

[9] https://www.insurancejournal.com/news/international/2022/02/26/655847.htm

[10] https://commercial.allianz.com/news-and-insights/expert-risk-articles/cargo-and-battery-fires.html

[12] https://ferryshippingnews.com/a-bold-decision-only-fossil-fuel-powered-vehicles-allowed-on-havila-voyages-ships/#:~:text=Havila%20Kystruten%20has%20decided%20only,on%20board%20the%20hybrid%20vessels.

[13] https://interferry.com/ferry-industry-facts/#:~:text=The%20global%20ferry%20industry%20is,cars%2C%20buses%20and%20trailers