The global supply chain is creaking under the strain of a series of heavy blows that have landed over the last two years. The COVID-19 pandemic, Brexit, the Suez Canal blockage, catastrophic weather events and the ongoing situation in Ukraine have cumulatively created a series of major roadblocks, which have illustrated how exposed many companies are to modern just-in-time supply chain frailty.

The insurance implications of all these business interruptions are significant. According to operational resilience firm Interos,[1] the average cost of supplier disruptions to organisations surveyed in 2021 was US$ 182 million. In this latest JENOA Insights article, we look at some supply lines that have been hit particularly hard and assess their impact on the reinsurance sector.

China crisis

Domestic sanitary policy in China at a regional level has had a considerable impact on the global supply chain. Chinese authorities continue to pursue a zero-COVID policy and during March and April 2022, provinces that cumulatively account for 25% of national GDP were under full or partial lockdown- that’s 7% higher than the worst week in 2021.

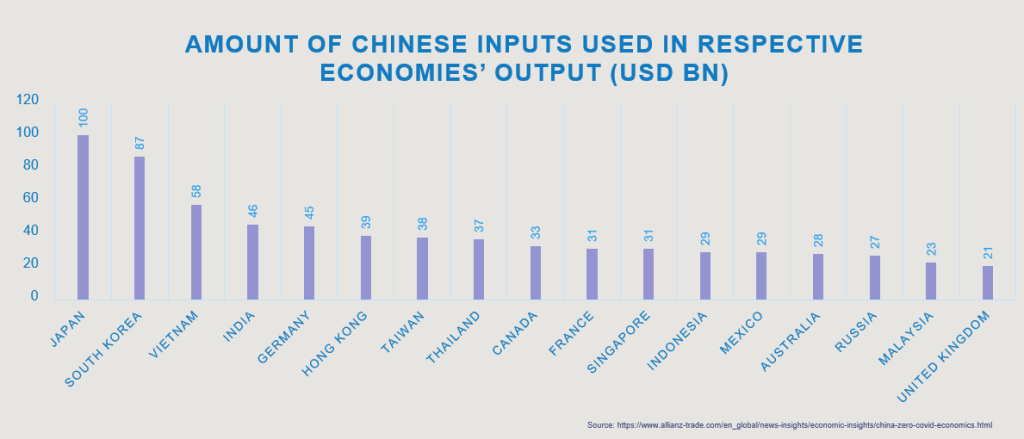

Such abrupt stops in local industrial output pose a continued risk to global trade, with approximately US$ 1.3 trillion of Chinese inputs used in the rest of the world, accounting for 1% of global output[2] (excluding China). The industries most affected by China’s provincial lockdowns are electronics and automotive, as well as renewable energy components such as solar panels.

With the inflationary pressures that come with a shortage of supply, material costs are rising and so are insurance premiums. Risk at the moment is largely dependent on the domestic health policies and restrictions implemented in China, especially at regional level. Some industry analysts predict a contraction in global trade volume for Q2 2022 as a result.

Solar panels under a cloud

The solar photovoltaic (PV) industry is experiencing supply chain issues that not only threaten planned green energy developments around the world, but also endanger the very business models on which they are predicated. According to the Institute of Supply Chain Management, 56% of the utility-scale solar projects planned for 2022 may have to be delayed or cancelled.[3]

Polysilicon, a key commodity into the production of solar panels, is concentrated in the Xinjiang region in the northwest of China. Industry estimates suggest that the region is responsible for 45% of global polysilicon manufacturing.[4] One of the reasons for this concentration is the cheap, coal-fired electricity on offer in the region, which represents a major cost in the production of PV panels. Adding to the pressure on global supply chains, customers in the US and EU are also subject to certain legal and regulatory restrictions on the import of polysilicon, thus reducing supply and availability as well as driving up costs. Furthermore, this underlines the need to be aware that risk can originate from a variety of angles.

It is estimated that the price of polysilicon has jumped by 175% in the last two years. Steel, which forms the racking that holds the PV modules together, has increased by over 200%, and weather conditions, as well as logistics bottlenecks, have forced the cost of shipping up by 500% compared to 2021.[5] With the added increase in fuel and labour costs, production costs for PV modules have risen sharply.

Higher unit cost means higher premiums, but do PV companies have adequate insurance to protect them from business disruption? Business Interruption insurance are generally covered following a physical damage such as fire and flooding, however we saw that following the pandemic, as a result if no physical damage the Business Interruption policy was unable to respond. he immediate aftermath of the pandemic.

Insurers are still reluctant to provide non-physical damage and this has become a major concern for Clients. In response a number of new Parametric solutions for Solar PV industry are being developed, but these are still relatively expensive and often do not provide the policy limits seen in conventional BI Polices.

Chips are down

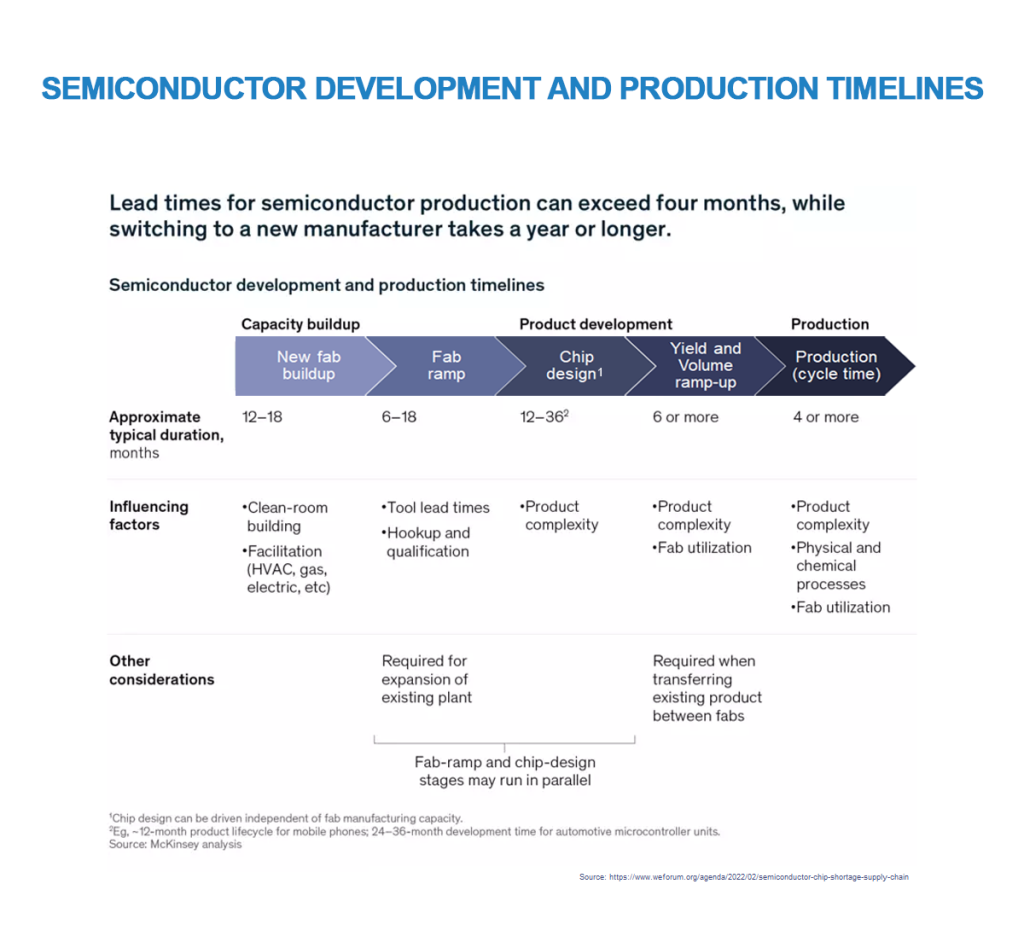

The semiconductor industry responds very slowly to change. The production process means that even increasing capacity to another manufacturing site can see lead times of six months, whilst the complexities of shifting to a different manufacturer can add one year to production.

So, when the virus went global in early 2020, the semiconductor market was thrown into turmoil. Automotive manufacturers, for example, were forced to slash chip orders in response to plummeting vehicle sales. However, later in the year demand for new vehicles increased much faster than anticipated, by which time semiconductor manufacturers had already pivoted, putting many production lines to work to satisfy demand for other applications.

Resetting the supply chain to feed the automotive industry will take some time.

With the semiconductor shortage holding back automotive manufacture, the shortage of new vehicles has seen a dramatic rise in demand and value.[6] A rise in the used car market has, in turn, seen vehicle replacement value increasing too, which also affects insurance premiums.

The shortage of replacement parts has driven automotive costs up too, leading to higher costs for repair and, therefore, insurance. Claims inflation driven by parts and labour inflation is having an upwards pressure of the overall cost of repairs to a flourishing used-car market, leading unavoidably to increased premiums.

Furthermore, delays to vehicle repairs caused either by parts shortages as a result of supply chain issues, or by high demand for services, has led to a dwindling supply of courtesy vehicles, all leading to higher risk and higher claims down the line.[7]

Need for insurance innovation

The lack of resilience in the global supply chain is creating a high level of risk that reinsurers will be required to mitigate. It’s not easy, however, as the insurance industry itself is struggling to understand and come to terms with the true level of exposure across the world. In many cases it is hard to cover the level of exposure some customers experience.

Business interruption will feature high among insurers’ needs when it comes to updating their product offerings. Extended cover has been a natural response among insureds to the pandemic, particularly where no physical damage is involved. Given the legal actions in the UK, customers are likely to need assurances as to how these kinds of claims might play out in other interruption scenarios.

New lines of business and innovative products are likely to help insurers meet the needs of exposed companies looking to mitigate at least some of the risk caused by unreliable supply chains. For example, products could be designed to foster a greater emphasis on resilience, as well as a shift from a global supply chain to more regional hubs.

Business leaders in MENA already have their eye on potential changes down the line. One CEO in the region[8] said that economies may need to focus on more local and regional resources – predicting a deliberate move away from dependence on major world economies like the US and China, and instead creating more resilient regional economic hubs that can diversify their supply chains. According to the Interos Annual Global Supply Chain report, companies plan to reshore or nearshore an average of 51% of existing contracts as part of supply chain reforms, with 64% of companies surveyed planning to make wholesale changes to their supply chain footprint.

One of the major problems that need addressing is that cover is in most cases only provided for tier 1 suppliers, often on a named-supplier basis only. When you consider that only about half of a typical company’s suppliers are evaluated during risk analysis, and only 10% of companies continuously evaluate supplier risk, that represents a major gap in coverage. Approximately 35% of supply chain disruption occurs in tier 2 or tier 3 suppliers.[9]

For example, if an earthquake cuts production at a major component manufacturer, business interruption cover will only soften losses if that manufacturer is a named tier 1 supplier. If, however, that vital component is manufactured by a producer in tier 2 or tier 3, insureds are generally not covered. Insureds therefore need to better evaluate their supply chains to identify key suppliers and assess the financial impact from a disruption to these supplies. In order to secure adequate insurance such tier 2 or 3 suppliers may need to be named specifically on an insurance policy.[10]

At the very least, companies and insurers should promote the development of distributed supply chains, built on multiple identified suppliers in alternative countries or hubs throughout the supply chain and considered against a background of increased risk analysis and supplier monitoring.

How long until normal service is resumed?

According to Morgan Stanley,[11] these serious restrictions in the global supply chain may be more fleeting than many are predicting. They argue that the single biggest culprit for supply chain issues was not the pandemic itself, but rather the unpredicted and unprecedented spike in the online demand for goods that arose from it, due to fiscal stimulus and social distancing. With trends now suggesting that services are gaining a greater share of consumer spend again, many of the pressures affecting supply chains may well dissipate.[12]

We will simply have to wait and see if that prediction bears out.

For the time being, insurance customers are likely to see sustained pressure on supply chains, and so will be looking for innovative solutions to product lines and cover to give them the guarantees they need against catastrophic losses.

[1] https://www.interos.ai/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Resilience-2022_Interos_Annual-Global-Supply-Chain-Report_5_11_2022.pdf

[2] https://www.allianz-trade.com/en_global/news-insights/economic-insights/china-zero-covid-economics.htm

[3] https://www.ioscm.com/blog/will-supply-chain-issues-scupper-the-solar-industrys-moment-in-the-sun/

[4] https://www.bernreuter.com/newsroom/polysilicon-news/article/opinion-creating-an-alternative-pv-supply-chain-is-no-cakewalk/

[5] https://www.ioscm.com/blog/will-supply-chain-issues-scupper-the-solar-industrys-moment-in-the-sun/

[6] https://www.independentgarageassociation.co.uk/news/how-supply-chain-issues-can-affect-motor-trade-insurance

[7] https://www.independentgarageassociation.co.uk/news/how-supply-chain-issues-can-affect-motor-trade-insurance

[8] https://www.cnbc.com/2020/05/05/coronavirus-golden-opportunity-for-reforms-in-gcc-economies.html

[9] https://connect.avivab2b.co.uk/documents/view/aviva_supply_chain_risk_management_lps.pdf

[10] https://www.zurich.co.uk/news-and-insight/avoiding-underinsurance-in-the-supply-chain

[11] https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/supply-chain-disruption-outlook

[12] https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/supply-chain-disruption-outlook