The world’s net-zero energy transition is well underway, with governments, energy generators, market players and consumers all playing their part as economies around the world grapple with the demands of the Paris Agreement and the UN COP climate conferences, to reduce carbon dioxide emissions whilst driving economic growth and prosperity.

Transport is a key part of government policy in developed economies seeking to address emissions and temperature targets. The sector is an easy target for naming and shaming, and certain ‘facts’ have come to characterise net-zero policies in developed economies – for example, the internal combustion engine is a ‘bad thing’, and EVs are ‘good things’ and much better for the planet.

Vehicle emissions are something everybody can get their head around. After all, there are few more totemic rituals, and few that more vividly embody our reliance on hydrocarbons, than the simple action of filling a vehicle with gas or diesel. Auto manufacturers and OEMs were quick off the starting blocks designing and mass-producing battery electric vehicles (BEV) and announcing phase-outs of ICEV production, confident that everybody would want their products because they were supported by central planning and generous taxpayer subsidies as a policy tool to encourage behavioural change.

Nevertheless, Q1 2024, has been dominated by worldwide headlines and press reports claiming that the EV market is in freefall,[1] and auto manufacturers and OEMs are now happily chiming in to confirm that sales are down, with some even going as far as to say that plans to phase out the internal combustion engine should be delayed or put on hold.

In 2023, Ford lost around US$ 65,000 on every EV it produced.[2] In the UK, despite encouraging statistics for EVs from commercial and fleet sales – heavily subsidised by taxpayer grants and tax incentives – the all-important behavioural-change target of the consumer retail market fell by 15% in 2023,[3] and by a similar proportion in Germany.[4]

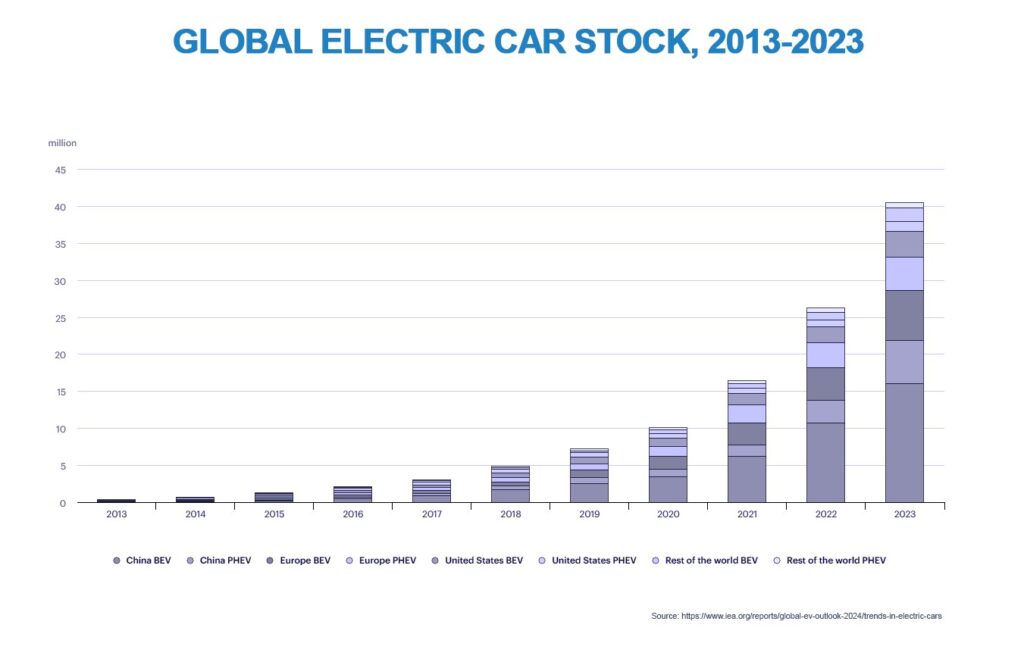

The UK government has already pushed back the planned phase-out of ICEVs by five years, from 2030 to 2035, and fifteen years after the first mass-market EV appeared in 2009,[5] global penetration has been sluggish, with the battery electric vehicle (BEV) accounting for less than 3% of the total global car stock.

But what is behind the downturn in BEV sales? And is it temporary or structural? Why have EV discounts increased by more than 200% since January 2023, as auto retailers struggle to clear their oversupply of EVs, if the private retail consumer market is as buoyant as industry and government would have us believe?

Here, we delve a little deeper to establish some of the economic realities behind the performance of the EV market and examine whether consumer preferences that have emerged as a brake on the energy transition in transport run deeper than anybody expected.

EVs: what are they for?

No tailpipe emissions are an attractive selling point, particularly for urban dwellers who tend to care more about local air pollution than general carbon dioxide levels. In theory, at least, the EV has been selected and agreed on by government and inter-governmental central planners as the only solution to reducing demand for, and reliance on, hydrocarbons. In turn, without the burning of hydrocarbons, transport policies like this will help reduce global CO2 emissions. By steadily reducing demand for refined hydrocarbon products, so the logic goes, the world can reduce its climate-warming CO2 emissions without losing any utility or mobility, and it can do so without enduring too much economic hardship.

Marketed and sold as ‘zero-emissions’ vehicles, the utopia of a distant future in which EVs are charged exclusively by power from renewables is now widely accepted as fact. Accepting at face value the technology selected by central planners in inter-governmental organisations and government departments, OEMs have been swept along in the rush of recent years to demonstrate a position on ‘sustainability’, keen to be seen to take on board the need to keep average global warming below the 2°C target of the Paris Agreement whilst remaining competitive in the lucrative US, European and Asian markets. Crucially, auto manufacturers are keen to maintain their market segment without losing out to more agile legacy ICEV producers or recent, all-electric disruptors such as China’s BYD, NIO and many others or America’s Tesla or Rivian.

The JENOA view

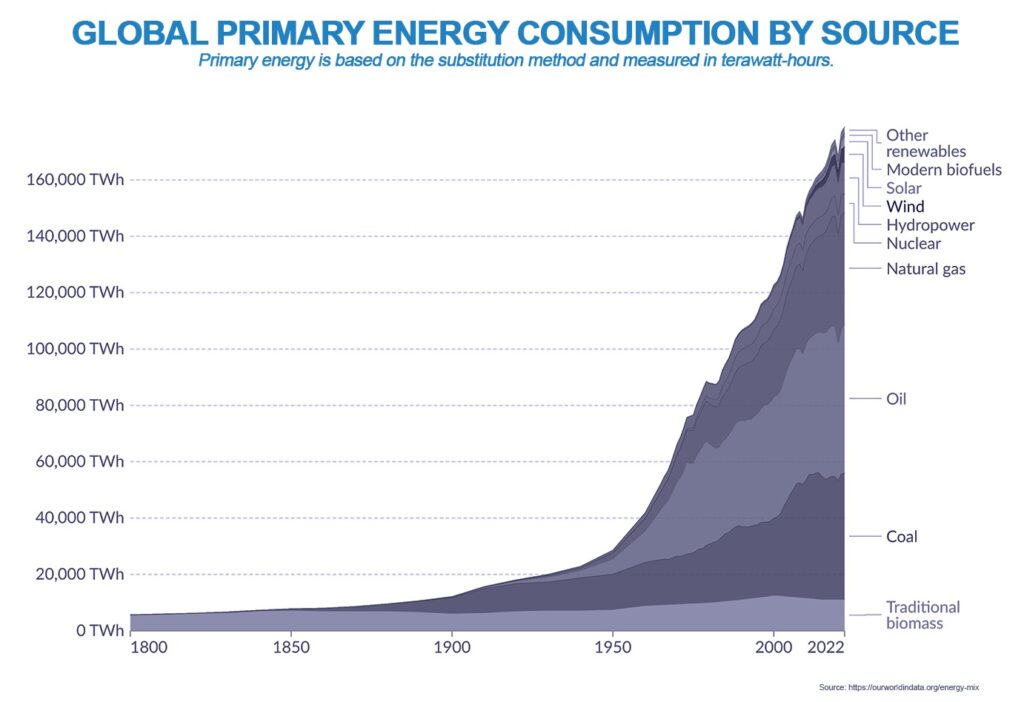

Despite the promised EV utopia of motorists enjoying cheap or free power in a future world where vehicles are powered by wind turbines and solar panels, the reality is that, as things stood in 2022, the vast majority of direct global energy consumption was provided by just three products: gas, oil and coal.[6] It is hard to defend the benefits of ‘zero-emissions’ motoring when hydrocarbons account for more than 80% of global per capita energy consumption. In other words, EVs are being charged by hydrocarbons. In China, which accounts for around 60% of all EVs sold worldwide,[7] hydrocarbons account for 86% of the total energy supply and over 80% of per capita energy consumption in the country.[8]

This reality has not bypassed the head of the International Energy Agency (IEA), Fatih Birol, who has publicly conceded that “electric cars will not save the climate”.[9] In fact, many observers have suggested that, even if the global market hits the IEA’s target for 2030 of 140 million BEVs and 65% of total global sales[10] – and that looks unlikely as 2022/23 figures reveal an estimated total stock of just 40 million – their effect on global emissions of CO2 will be disproportionate to the pain and cost of electrifying the global car stock, as all transport, including shipping, haulage and aviation, accounts for just 15% of total global CO2 emissions.[11]

Given that the IEA bases its assumptions on an optimistic methodology that overlooks emissions monitoring gaps and problems in the EV supply chain,[12] the benefits to private buyers are beginning to wane as the voting public begins to appreciate the tough calculus involved in determining the true embodied emissions in EV production, where the market is dominated by players in China, whose economy relies disproportionately on fossil fuels.

Early success in the retail consumer market was largely driven by early adopters, with the market becoming ever more saturated with each passing year, and by commercial and fleet sales, where the EV market is driven largely by government and manufacturer incentives, not consumer retail demand. For example, in the UK, a country that likes to position itself as a ‘climate leader’ since Prime Minister Boris Johnson famously championed the environmental cause during his premiership and COP26 leadership, incentives include purchase discount subsidies, vehicle excise duty and road tax surcharge exemption, generous capital allowances, ‘benefit-in-kind’ income tax exemptions, fuel duty and fuel VAT exemptions and congestion-charge exemptions.

The retail consumer market remains sceptical of the climate benefits of EV adoption and is also becoming increasingly resistant due to the unnecessary financial hardship that EV ownership entails – insurance premiums rose by more than 70% in 2023 on the back of persistently higher repair costs, expensive personal-injury claims and extended off-road time.[13]

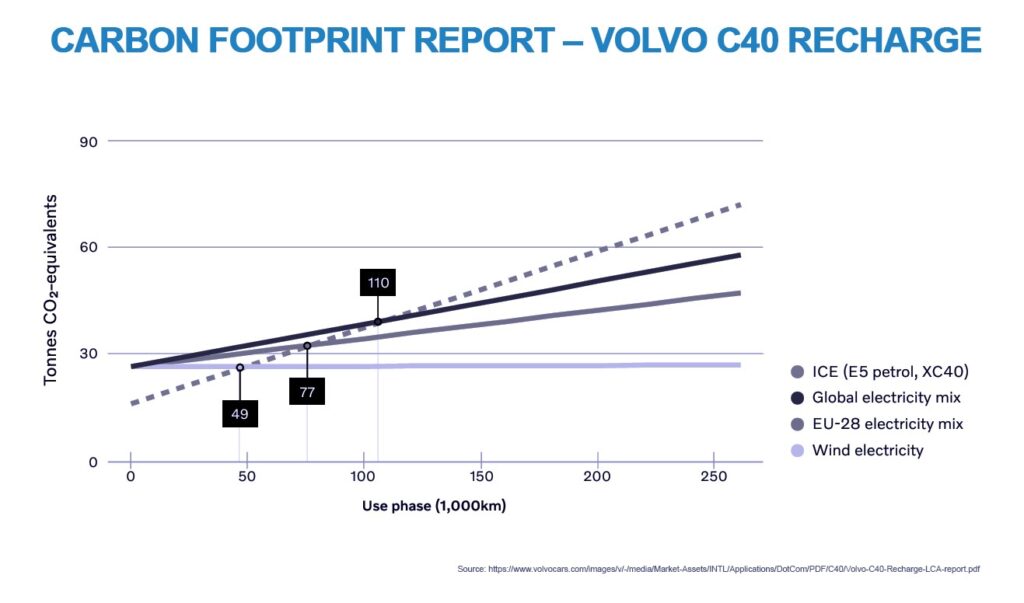

In addition, private buyers are subjecting potential EV purchases with increased scrutiny, given the extra investment and uncertainty around the second-hand market and residual values of an untried technology. Swedish auto manufacturer Volvo recently conceded that its C40 Recharge product does not reach the emissions payback period[14] from its inherent production and manufacturing emissions until after 110,000 km.[15] With uncertainty around longevity, replacement age and scrappage age for the untested second-hand EV market and a paucity of long-term data, the figures are not convincing for everyone to consider a dramatic change in habits and lifestyle.

In Q1 2024, Hertz announced plans to shed at least one-third of its EV fleet and replace them with petrol vehicles, citing consumer preference, high repair costs and plummeting value. Among OEMs, General Motors, Stellantis, VW, Daimler[16] and Ford have announced plans to scale back production targets.

Yet, despite what some commentators see as an emerging reality, other observers of auto trends claim that 2024 will end up as little more than a blip on an upward sales trajectory. According to Schmidt Automotive Research, EV sales in Western Europe will briefly stagnate in 2024, but encouraged by tightening EU CO2 rules, will jump in 2025 to 2.6 million (20%), and on to 9.2 million or 65% by 2030.[17] Whether this turns out to be a prescient market analysis is too early to say.

What does this mean for MENA clients, and how can JENOA help?

JENOA has vast experience helping automotive clients in the MENA region and has long associations in the auto trade. By offering access to the Lloyd’s of London market in addition to all reinsurance hubs around the world, we are able to leverage established Lloyd’s capabilities alongside international reinsurance to help clients prepare for a period of uncertainty and readjustment in the automotive sector, and to mitigate risks of business interruption and market downturns. In short, JENOA has the capabilities to meet emerging challenges in the sector. With a strong focus on insurtech, our end-to-end digital brokerage offers a much broader reach into markets in MENA and further afield, as the world shows signs of hesitation on its transition towards any bridging technology that might one day result in lower fossil-fuel use.

Whilst inflation and a steep rise in the retail cost of new cars has added to premiums in every auto segment, resulting in UK auto insurance rising by 25% in 2023 after a staggering 50% rise in 2022, there is growing evidence from the auto trade and auto press that underwriters have insufficient data on the EV manufacturing sector to adequately price risk.[18]

Thatcham, the industry-funded UK research centre notes that the growing number of unknowns are adding to auto insurance costs across the board. “We’ve had steel or aluminium-bodied cars, internal combustion engines, and the same layout for the best part of 100 years. Now, ‘normal’ could mean £15,000 Far Eastern electric car with a sodium battery,” says Thatcham’s Head of Automotive, “writing the car off, because the labour cost makes it unviable.”[19]

With very little data on how much damaged battery packs can cope before the risk of fault or fire increases, underwriters and insurers are in the dark when it comes to pricing risk. As a result, they add a sum onto every auto premium – BEVs, MHEVs, hybrids and petrol and diesel cars – and the whole auto insurance market rises.

JENOA has the capability to address these problems, by offering a comprehensive review for logistics, transport and haulage companies and many other organisations with large fleets, to resolve many of the issues that are driving EV and ICEV insurance to unprecedented highs. JENOA’s insurtech focus also puts us at the cutting edge of data analysis when it comes to producing innovative insurance solutions and industry-wide cooperation to address the vast disparities in international manufacturing standards and OEM repair guidelines.

As Thatcham’s Head of Automotive notes, “all an insurer can do is underwrite the risk it sees. If it can’t understand a risk, it has to price that risk appropriately. So if somebody says ‘here’s a £35,000 battery, but if the airbags deploy we can’t tell you if that battery is safe or not,’ then an insurer has no choice. An accident that deploys the airbags increases the risk the car will be a total loss.”

The end of the road?

Are consumers becoming savvier about widespread environmental claims about the benefits of an EV transition? As mentioned above, Volvo claims there are no emissions savings until 110,000 km,[20] or 8.25 years after purchase, based on long-term mileage data,[21] on a global electricity mix dominated by unabated fossil fuel use in major industrial nations. In other words, for more than half of its useful lifespan, an EV will be responsible not just for the high embodied emissions in production, but for placing extra demand on a global power grid still dominated by hydrocarbons.[22]

When it comes to the private retail consumer market, the question remains: how long can taxpayers in developed economies continue with generous subsidies, incentives and tax breaks, especially when a positive EV sales trend seems to rely almost exclusively on government sweeteners to encourage uptake?

It may transpire that 2024 ends up as an unfortunate blip on the sales graph, but with US interest rates currently at a 23-year high of 5.5% and global inflation at around 6% in 2024, something transformative is going to have to occur in the EV market to keep on track with the IEA’s 2030 and 2050 targets.

State-led industrial strategies rarely pan out as planned. BEVs still have a chance to gain meaningful market share before technologies such as synthetic fuel or hydrogen cells overtake and supplant them. However, a viable business model is clearly elusive, and consumers remain unconvinced that, even if a viable model is found, it should be prioritised over more affordable and effective efforts elsewhere to achieve desired CO2 reductions.

[1] https://media.ford.com/content/fordmedia/fna/us/en/news/2024/02/06/fourth-quarter-and-full-year-2023-earnings.html

[2] https://media.ford.com/content/fordmedia/fna/us/en/news/2024/02/06/fourth-quarter-and-full-year-2023-earnings.html

[3] https://www.which.co.uk/news/article/big-drop-in-new-electric-car-sales-to-private-buyers-aJrQL4D3105T

[4] https://www.carscoops.com/2024/04/q1-ev-sales-drop-14-1-percent-in-germany-tesla-sales-tumble-37-percent/

[5] https://www.nissan-global.com/EN/DOCUMENT/PDF/AR/2012/AR2012_E_p13_EV_History.pdf

[6] https://ourworldindata.org/energy-mix

[7] https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2023/trends-in-electric-light-duty-vehicles

[8] https://www.iea.org/countries/china/energy-mix

[9] https://spectrum.ieee.org/the-ev-transition-explained-2659316104

[10] https://www.iea.org/energy-system/transport/electric-vehicles

[11] https://www.iea.org/energy-system/transport/electric-vehicles

[12] https://manhattan.institute/article/the-tough-calculus-of-emissions-and-the-future-of-evs

[13] https://www.fleetnews.co.uk/features/the-future-of-evs-cost-of-production-to-fall-but-repair-bills-to-soar

[14] The emissions payback period is an accepted term for the period of time it takes for the manufactured (and in theory lower-carbon) product to start to make a positive contribution to net emissions reductions. High embedded emissions in manufacturing take time to offset with lower-carbon products over their lifetimes, but as evidence shows, in certain scenarios, this may never actually happen, making the production and use of an electric vehicle dirtier in terms of emissions than a petrol-engine vehicle.

[15] https://www.volvocars.com/images/v/-/media/Market-Assets/INTL/Applications/DotCom/PDF/C40/Volvo-C40-Recharge-LCA-report.pdf

[16] https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/mercedes-benz-hits-cars-returns-forecast-inflation-supply-chain-costs-bite-2024-02-22/

[17] https://www.forbes.com/sites/neilwinton/2024/01/16/european-ev-scepticism-could-derail-massive-sales-targets/?sh=d9b68386f851

[18] https://www.autoexpress.co.uk/car-insurance/97500/why-car-insurance-so-expensive-truth-about-rising-cost-insuring-your-car

[19] https://www.autoexpress.co.uk/car-insurance/97500/why-car-insurance-so-expensive-truth-about-rising-cost-insuring-your-car

[20] https://www.volvocars.com/images/v/-/media/Market-Assets/INTL/Applications/DotCom/PDF/C40/Volvo-C40-Recharge-LCA-report.pdf

[21] https://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/electriccars/article-13145619/Britains-EV-owners-annual-mileage-petrol-diesel-cars.html

[22] https://ourworldindata.org/energy-mix