The United Nations’ perennial climate-change conference, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of the Parties (COP), kicked off in Dubai, UAE, in November 2023, under the guise of COP28.

Now that the dust has settled, we would like to analyse what this conference has meant for Insurers across the Middle East. Some analysts have claimed it amounted to little more than a green light for the hydrocarbon industry,[1] while others hailed the transformational nature of a conference that, for the first time in its history, managed to insert the term “transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems” into the final communiqué[2].

The truth, we believe lies somewhere in between. The final communiqué was carefully worded, and although headline-grabbing initiatives seem to have pleased climate activists – for example, countries pledged US$700 million to kick off the Loss & Damage Fund,[3] which essentially socialises insurance premiums for vulnerable developing nations across global taxpayers – petrostates will be satisfied that the wording was sufficiently ambiguous and vague to allow a continuation of both unabated and abated hydrocarbons in the form of natural gas and oil.

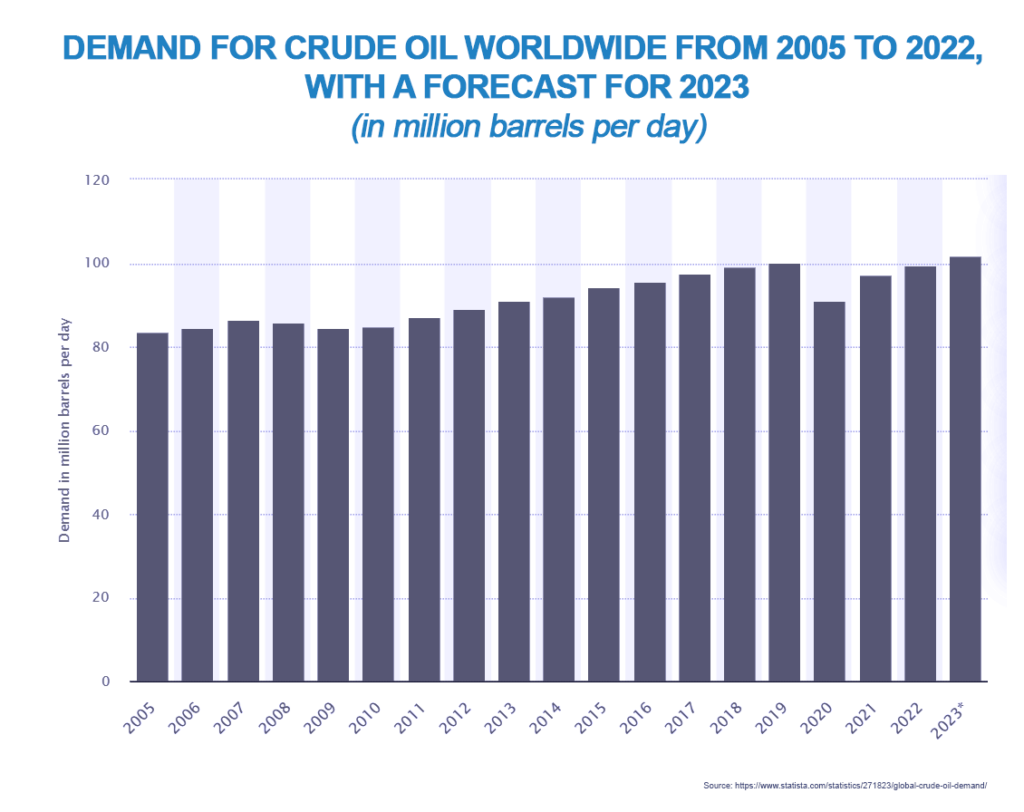

Beyond the headlines, however, opportunities for GCC insurers and reinsurers, from both an underwriting and investment point of view, look promising. Premiums and asset returns in upstream oil and gas remain strong,[4] and massive potential growth in the development of carbon capture & storage (CCS) – where the GCC region is already well advanced – presents a double win for insurers and investors alike. Furthermore, an opening up of new markets in a developing world that has suffered historically low penetration, subsidised by taxpayers in developed economies, looks set to provide an industry that understands how to profitably price risk, with a bonanza in natural catastrophe premiums for decades to come.

Here, behind the contradictory headlines, we delve a little deeper into what COP28 really means for the region, examining its implications for insurers and identifying potential growth opportunities in the future.

COP28: the subtext

Did COP28 really amount to business as usual for the hydrocarbon and insurance industries?

COP28 President Sultan Al Jaber used wording that reflected the phase-out of hydrocarbon emissions, rather than of fossil fuels themselves,[5] which is perhaps unsurprising, given the region’s leading global role in carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies.

In a carefully worded statement, COP28’s final communiqué called for “transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems”. It is worth noting that it specifies only energy systems; it makes no reference to transport, agriculture, domestic heating, or plastics, for example, and the very specific phrasing alluding to “transitioning away from” rather than “phasing out”, as many activists have long called for, places the onus squarely on the demand side rather than production side.[6]

Those disappointed with the outcome of COP28 claim that the conference’s final declaration was tantamount to a green light for the hydrocarbon industry. Such activists can be forgiven for arriving at this conclusion; natural gas will continue to perform the heavy lifting in the requirement for “transitional fuels”, even if the communiqué deliberately failed to offer a definition of transitional fuels. As Bloomberg’s energy and commodities correspondent, Javier Blas, notes, “it opens an enormous backdoor to support the use of natural gas for years, if not decades, to come. So perhaps COP28 marked the sunset of the fossil-fuel era, only to herald the dawn of the “transitional fuel” era — in the form of transitional gas”.

COP28’s final communiqué also called for an “orderly transition”, which allows both the US – now the world’s largest oil producer – as well as OPEC+ countries, to make the case that an orderly transition requires continued investment in new oil fields. An orderly transition, after all, is diplomatic speak for the overriding need to keep oil prices stable, something that is impossible without continued investment.

Given that around half of OPEC members are oil-producing jurisdictions in the MENA & GCC region,[7] can we expect an increased appetite and capacity for hydrocarbon projects in the future, both from an underwriting and investment point of view? Will future trends in hydrocarbon underwriting and investing follow 2023 trends, which saw a majority of the world’s largest insurers continue to underwrite new oil and gas projects?[8]

The JENOA view: opportunities & risk for GCC insurers

Oil & gas

To answer the question above, we need to look a little deeper into current trends in oil and gas insurance, to gauge the current appetite amongst insurers to take on what climate activists refer to as stranded assets. It is an important question to pose, not just for insurers in oil and gas in the medium term; beyond the immediate investment and premium returns available, it will give an indication of whether continued “abated fossil-fuel use” may or may not offer opportunities for dramatic growth in carbon capture and storage for the region.

Despite high-profile announcements from some insurers in 2023 that they would withdraw from oil and gas, virtually all insurers continue to offer cover for new midstream and downstream infrastructure. While high-profile 2023 withdrawals from fossil fuels made headlines, they included special provisions for the exclusion of new upstream projects.[9] According to market intelligence monitor Insuramore, insurers and reinsurers earned over US$ 21 billion last year from insuring coal, oil and gas projects, with insurers in the Lloyd’s of London market representing the world’s largest underwriters of hydrocarbon projects, with over US$ 2 billion in annual premiums.

Around 80% of the world’s 30-largest insurers and reinsurers remain committed to supporting upstream, midstream and downstream hydrocarbon projects into the future. Given COP28’s veiled recognition of natural gas as an important and necessary transitioning fuel, it is doubtful that insurers’ appetite for hydrocarbons will wane any time soon, and it appears that the insurance industry has little regard either for activists’ warnings of stranded assets, or for political cartels pressuring public companies to withhold cover. After all, natural gas now has the unofficial stamp of approval from the world’s premier climate agreement, or at least deliberately opens the door to that interpretation. As Bloomberg notes, “just don’t say it out loud”.

So where does that leave us? Has COP28, far from ushering in the sunset of hydrocarbons, laid the ground for concentrating on emissions abatement rather than fossil-fuel use? Does it signal an underlying acceptance that preserving global wealth and economic development with continued hydrocarbon use can live comfortably alongside emissions abatement?

As Oxford University’s professor of geosystem science, Professor Myles Allen points out, “as a matter of topology … we will still be using fossil fuels, fully abated, meaning 100% capture or recapture and permanent disposal of all the CO2 they generate, at the time we achieve durable net zero emissions. The only argument is how much”.[10] That being the case, the medium-term future points to significant opportunities available to insurers and reinsurers in the region in both investment returns and premium earnings.

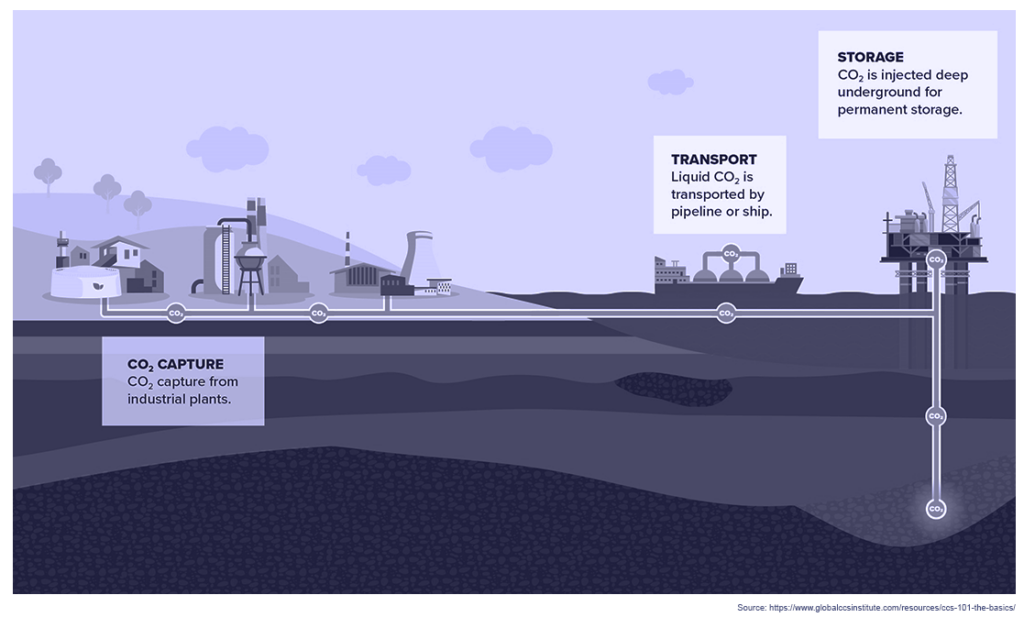

Carbon capture & storage

The scenario above could offer new investment and premium potential in the Carbon Capture & Storage (CCS) industry of the future, where existing capacity to abate hydrocarbon CO2 emissions will need to be scaled up by at least two orders of magnitude – or around 100-300 times the existing capacity – to abate emissions from the continued requirement for fossil fuels. As far as COP28 and CCS goes, the communiqué referred to “accelerating zero- and low-emission technologies, including, inter alia … renewables, nuclear, abatement and removal technologies such as carbon capture and utilisation and storage”. As Oxford’s Professor Allen asks, “does this text leave the door open to a future in which we just carry-on using fossil fuels and reinject the carbon dioxide they generate back into the earth’s crust?”

With just a few carefully chosen words, the UN has approved and rubber-stamped a technology that many hard-core environmentalists and climate activists claim, perhaps incorrectly, is still grossly immature. Those same critics claim CCS will be incapable of sequestering enough carbon dioxide to make any meaningful difference, in the hope of refocusing the spotlight back on the task of reducing fossil-fuel use. Earlier drafts of COP28’s final communiqué had emphasised that CCS was a means to transition away from hydrocarbons, but by the time the final declaration had been agreed, the emphasis on transition had been omitted.

Either way, whether climate activists’ claims that CCS will not be able to remove and store all the carbon dioxide fossil fuels produce will depend entirely on the industry’s ability to massively scale up in very short order. As mentioned above, estimates of growth in removal and storage capacity range between 100 times and 300 times existing capacity, but non-state oil enterprises like Exxon Mobil – which account for just 20% of global oil reserves[11] – have betted heavily on carbon-sequestration technology as a means of abating fossil-fuel emissions as part of their individual sustainability strategies. The wording of COP28’s communiqué has therefore been seen as another big win for private oil and gas companies; as Oxford’s Professor Allen points out, “as governments at COP28 have recognised, whatever happens now, we need to fix fossil fuels before we phase them out”.

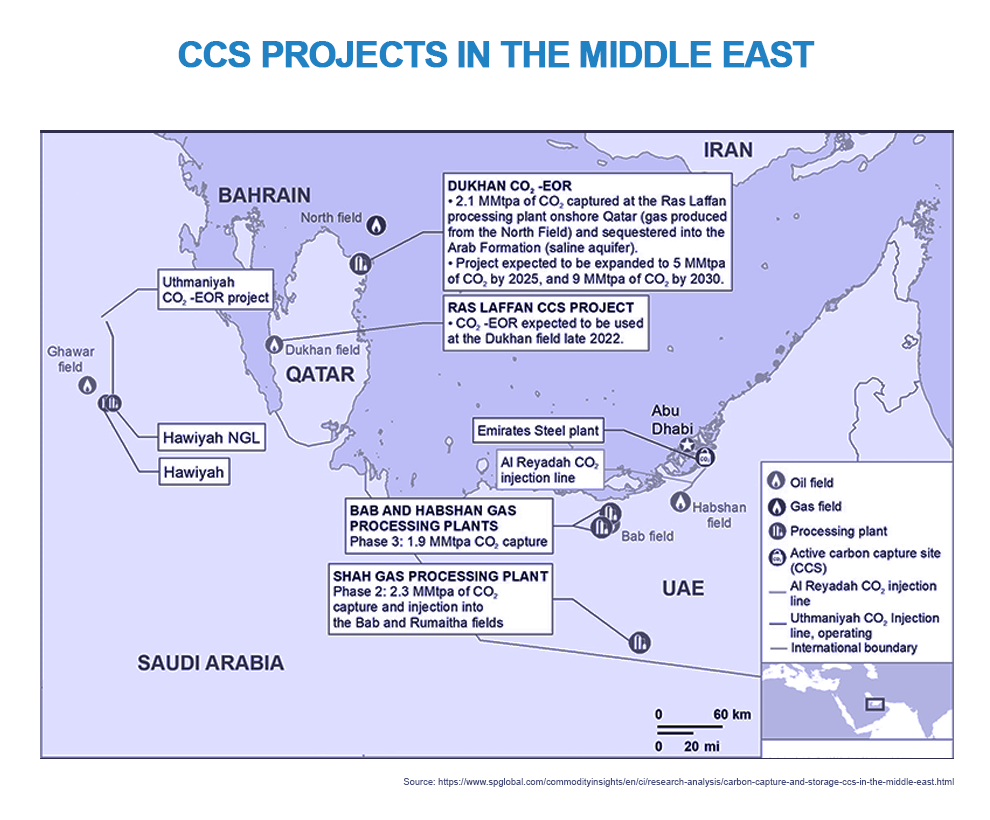

Not only is CO2 removal and storage (CCS) already well developed in the GCC; the MENA region is also incredibly well suited to CCS and has a long history of using enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques[12] – the process of injecting carbon dioxide into underground oilfields to maximise and increase volumes recovered from fields – which served as the precursor to modern CCS. Its geology is ideally suited to storing CO2 at underground depths of over 800 metres in depleted oil and gas fields and saline aquifers, geological features that represent prime sites for reliable storage, and its current capacity represents around 10% or more of all global CCS capability, with new projects for the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Qatar recently announced.

The CCS pipeline is highly likely to develop exponentially; national oil companies will want to position themselves among the most price- and CO2-competitive producers of the oil that will be needed in all transition scenarios. CCS gives GCC state oil companies the opportunity to maximise oil and gas reserves while slashing emissions.

It is perhaps no surprise that CCS is likely to form a major part of strategic transition planning in the region, especially given its more central role after COP28. With the region’s long history of successfully attracting project finance to develop large projects and its favourable regulatory and approvals regime, the investment and premiums earning opportunities from even a ten-fold increase in GCC CCS are impressive. If the technology develops at the pace needed to keep global warming below 2⁰C, whilst also harnessing oil and gas for GDP growth and global development, increasing global CCS capacity from 45MMtpa (million metric tonnes per annum) CO2 to 450MMtpa could place MENA reinsurers at the very heart of a new global gold rush.

Loss & Damage Fund

As mentioned above, the “operationalisation” of the UN’s Loss & Damage Fund, initially launched at COP27,[13] was hailed as one of the great success stories of COP28. Pledges made from a variety of nations at COP28 amounted to a little over US$ 700 million, but there are indications that those behind the initiative expect ultimately to be able to raise more than 100 times that figure, or around US$ 100 billion.[14]

The aim of the fund is to assist developing nations that are particularly vulnerable to the ill effects of weather-related disasters, and it will include global initiatives to launch or expand insurance solutions in these locations. In short, the fund will cover the costs of funding insurance premiums, borne by taxpayers in the richest nations, to offer protection from weather disasters to governments and citizens in the least developed ones. This plan is not without controversy in some quarters, however; there is a widespread belief that any cash in the Loss & Damage Fund should be used for longer-term investment, such as adaptation and disaster-risk reduction, rather than to exclusively finance insurance premiums.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the insurance industry came under the spotlight at COP28, with no less a figure than former US Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, claiming in a speech at the conference that “we need to rethink the insurance industry”, accusing it of closing its doors to those who needed cover the most.

However, the CEO of broking group, Howden, pointed out to COP28 that, “there seems to be a belief that the climate risks for vulnerable countries in the global South are uninsurable. The problem isn’t that they’re uninsurable, it’s that there has been nobody to pay the premium at the scale required.”

Indeed, as Insurance Times notes, “insurers are like any commercial organization – they will sell you the product you require. Nothing is truly uninsurable, it is just a question of whether you are willing to pay the price”. In the Loss & Damage Fund, it seems, we have found wealthy, developed economies that are now willing to write large, if not blank, cheques to subsidise those premiums at the scale required. It is a matter of public record that, despite launching the Loss & Damage Fund at COP27, nobody had taken the trouble to model the risks in individual vulnerable countries until 2023, meaning that the fund was launched with no risk data, and no credible idea of how much might be needed to protect them.

Some modelling on the vulnerability of these developing nations has now been undertaken in partnership with broking group Howden,[15] but it remains the case that many of this project’s assertions – for example, that vulnerable nations across the Pacific, Caribbean and Indian Ocean face foreseeable losses of between 50% and over 100% of annual GDP from climate-change events such as severe droughts, tropical cyclones and floods – run counter to the IPCC’s most recent scientific assessments. These assessments refute the notion of any man-made climate change signal detectable in hydrological, ecological or agricultural droughts, floods or tropical cyclones in those areas[16] under current trajectories. In addition, we already know that weather losses as a percentage of GDP are showing a downward long-term trend, with that trend more acute in low-income countries than in high-income developed nations. Indeed, it is this kind of vague analysis that Lloyd’s of London may have had in mind when its Head of Markets noted last year that the insurance industry’s analysis of climate change and natural catastrophe losses came from a “vested interest perspective”[17] and was “wrong and lazy”. He added that it was vital the industry was “on top of the latest science”.

Either way, regardless of the frequency of future extreme-weather disasters or their cause, open-ended funding to bridge the protection gap in vulnerable, less developed nations, particularly in the southern hemisphere, is excellent news for insurance providers across the world; it offers GCC and MENA insurers and reinsurers opportunities to grow natural catastrophe lines in new and previously underserved markets.

COP28: good news for MENA & GCC insurers

Whilst the public face of COP28 strived to present a united front in its efforts to walk away from an industrial model that has served successful modern economies well for a century and a half, the private face acknowledged that the path to keeping temperatures below 2⁰C is more complex, nuanced, difficult and costly than many of the headlines let on.

COP28’s tacit acceptance of the need for fossil fuels well into the future is likely to enhance potential investment and premium earnings for regional MENA, GCC and global insurers and reinsurers for decades to come. In short, there is a growing realisation that high investment returns and high premium income from an industry that continues to supply the vast majority of the world’s direct primary energy consumption[18] are more resilient to political pressure than was previously acknowledged.

That said, the growing need to abate emissions from the use of hydrocarbons presents further opportunities for a region ideally suited to growth in this sector, and one that offers a favourable approvals and regulatory environment for new industries like CCS to grow rapidly.

Coupled with a dramatic increase in natural catastrophe lines for developing nations vulnerable to extreme weather, in the form of the Loss & Damage Fund, GCC insurers are well placed to take advantage of these opportunities.

[1] https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/12/global-what-happened-at-cop28-essential-need-to-knows/

[2] https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2023-12-13/climate-emergency-does-cop28-mark-the-beginning-of-the-end-for-fossil-fuels

[3] https://www.genevaassociation.org/publication/climate-change-and-environment/cop28-key-messages-and-implications-insurers

[4] https://www.energymonitor.ai/finance/risk-management/insurers-double-down-on-fossil-fuel-projects-despite-record-climate-disaster-payouts/?cf-view

[5] https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2023-12-13-expert-comment-it-remarkable-how-much-we-agree-cop28-and-transition-fossil-fuels

[6] https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2023-12-13/climate-emergency-does-cop28-mark-the-beginning-of-the-end-for-fossil-fuels

[7] https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/25.htm

[8] https://www.energymonitor.ai/finance/risk-management/insurers-double-down-on-fossil-fuel-projects-despite-record-climate-disaster-payouts/

[9] https://www.allianz.com/content/dam/onemarketing/azcom/Allianz_com/responsibility/documents/Allianz-Statement-oil-gas-business-models.pdf

[10] https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2023-12-13-expert-comment-it-remarkable-how-much-we-agree-cop28-and-transition-fossil-fuels

[11] https://thebreakthrough.org/journal/climate-change-banned-words/big-oil-villains-climate-change?

[12] https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/middle-east-enhanced-oil-recovery-market

[13] https://www.genevaassociation.org/publication/climate-change-and-environment/cop28-key-messages-and-implications-insurers

[14] https://www.insurancetimes.co.uk/analysis/briefing-cop28-becoming-all-fund-and-games-for-insurers/1447309.article

[15] https://www.reinsurancene.ws/risk-sharing-systems-can-scale-up-ld-funds-to-support-climate-vulnerable-countries-report/

[16] https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/chapter/chapter-12/

[17] https://www.insurancenews.com.au/daily/a-little-bit-lazy-lloyd-s-chief-criticises-climate-change-claims-narrative

[18] https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-primary-energy